Game design patterns (and not programming design patterns) are holy scriptures for aspiring game designers. They are these little nuggets of game design knowledge and ready-to-plug design bits that are easily learned and feel safe to use. I remember trying to assimilate as many as I could in my younger days, thinking that this was what would make me a great game designer. And it partly did, until I made mistakes I didn’t understand (or worse, didn’t notice until much later). I also recall, during an interview for a game director position for one of the biggest game companies in the world, an exec asking me to “list the best design patterns I am using on all my projects and why”. As if they could be ranked, and knowing the S-tier, secret patterns would make me more worthy of the position (spoiler alert: it does not).

Design patterns get taught like recipes, or plug-n-play magical bits of design: “Add a hub”, “Make a crafting system”, “Give enemies attacks telegraphs”, “Implement a battle pass”, “We need a checkpoint system”. That approach is enticing because it turns design ambiguity into a to-do list, and for a designer, controlling chaos is oh-so-sexy: just follow the recipes, and you will make a good game. But doing so often produces a particular kind of failure: stacking recipes you do not fully understand creates inconsistent, muddled experiences that are a pain to fix.

Design Patterns aren’t magical one-size-fits-all solutions. They are solid, stable responses to recurring constraints, coming from either the development or the player: content limits, information overload, pacing balancing, economy stretching, players’ skill distribution, social friction… And it’s only when you clearly identify the constraints you are trying to solve that you will find the right design pattern to employ, or better, that you will find your own answer instead of unfolding a textbook pattern. Failing to do so will instead create friction, impossible-to-balance games, development hell, and chaotic player experiences.

I could have made this article a “Top 10 Design Patterns Every Designer Should Know”, but not only would this be of no help to you, but it may also continue this false narrative that they are the answer to all of our design problems. Instead, we’ll try and have a look at how we can solve our problems using design patterns as a framework.

The Danger of Treating Design Patterns as Recipes

In my experience, there are usually 3 dangerous reasons a team would turn to a design pattern:

- Coordination and alignment: It gives teams a common vision to discuss. “Hub” is easier to plan and align on than “a pacing recovery mechanic that manages content accessibility and gating.”

- Risk management: A solid pattern feels safer (planning, QA, iteration time) than inventing a new system, particularly when under development pressure.

- Competition imitation: “Every game in my reference is doing it, I’d better do it as well”.

In themselves, these reasons stand, and we can find many situations where these would be proper (complex team structure, time to market, player expectations and marketability…). Yet, these reasons aren’t sufficient, and they often critically underthink how drastically the addition of a new pattern will affect the player experience. Design patterns aren’t simple features; they are a trade, a conversion machine, if you will, that will solve a problem by accepting a cost somewhere else: in agency, clarity, pacing, fairness, development time, surprise. Examples:

- “Soft Gating” our content (skill/progression-based, rather than “Hard Gating”, the classic lock & key approach) can reward mastery and expand player agency, but it risks sequence-breaking our narrative and frustrating players if consequences aren’t signposted enough.

- Fail-Forward mechanics prevent the problem of failure “deleting time”, but risks softening the stakes and blunting the sense of achievement players should feel.

- Rubber-banding systems are great at creating tight, exciting races from start ot finish, but may rob players of their victory and dismiss their skills by “cheating”.

Adding a design pattern to our game without understanding it fully in your unique context puts us in a situation where its impact will be felt later in production (or when the game is live) and where solving it could be extremely complex and, more often than not, very expensive: we would inherit the costs of each pattern without earning its benefits, because we never adopted the constraints that made the pattern coherent in the first place

So let’s dive a bit into what a design pattern is, what it implies, and how it affects the player experience.

Design Patterns

Let’s start with a single, usable definition of what a design pattern is:

A design pattern is a repeatable structure that addresses recurring constraints by shifting costs while shaping player expectations.

So… We have a lot to unpack here, and the parts in bold will be central to our study:

- Repeatable Structure: what makes the design pattern: the mechanics, content, rules, or flow that this pattern follows. Example: “Telegraphed attacks” implies perceivable cues (animation, VFX, SFX…), a readable window of opportunity, a clear expected reaction, and an unambiguous resolution. This structure supports itself on clear levers (why does this pattern work). Example: information > prediction > perceived fairness.

- Constraints: the pressure points, limitations, or problems we are trying to solve with this pattern. Example: limited player attention, calculation complexities, early churn, pacing/intensity range gap, economy inflation, production time, etc.

- Costs: the downsides we are accepting in exchange for the pattern benefits: these could be production-facing or player-facing. Example: reduced surprise, increased grind, balance complexity, development time, more complex onboarding, etc.

- Player Expectations: the implicit promise the game is making to the player through the use of this design pattern. Even unintentionally, every feature signals to players what to expect from the game. From now on, we will call them Contracts. Examples: “Even if I lose, I make progress”, “If I pay attention, I will succeed”, “The UI always shows me what matters”, “If I play a little bit every day, I will make steady progress”, “Preparation is the key to mastery”, etc. These contracts are fragile, easily broken, and will lead to loss of trust from the player and a damaged experience if ignored.

These are the key factors that dictate whether a design pattern should be used, and why starting with a textbook pattern is often a bad idea. In most cases, this is a bottom-up approach. Too often did I hear sentences like “We are a Live game, so we need a Battle Pass” or “This is a genre staple, we can’t ship without a crafting system”, without properly understanding the ramifications these decisions will have on the game and its development.

Instead, let’s start the other way around: What constraints is our game under? What costs can we afford? What contracts are we willing to sign with our players? These are the real questions that will let us find what design patterns make sense to use or bend in order to create a unique, cohesive experience.

From Pressure to Feature: a Constraint-first Framework

#1: Write the Constraint(s) you are facing without mentioning Features

Before discussing solutions, it is critical that we start expressing the constraint(s) we are trying to solve, precisely. Doing so will define a clear design space for us to explore.

Example, instead of “we need a crafting system”:

- “We need a durable motivation loop between content drops”.

- “We need to prevent players from feeling idle during downtime”.

- “We need progression depth without moment-moment paralysis”.

- “We need players to feel failures without losing anything important”.

- Etc.

Notice how different all these constraints are? A crafting system is only one possible answer to a wide array of problems! You may have also noticed that in none of those did I mention specific features: we want to define the design space of our constraint without shoehorning solutions.

#2: Write the Contract(s) you are willing to sign with your Players

Whether we want it or not, every feature of our games signals behaviors to our players, something to expect. It is critical to identify these contracts early so we can shape the features around them and not let the game dictate them to us.

If we continue the previous example, contracts for these constraints could be:

- “Even a short session still creates meaningful progress”.

- “Downtime is a different kind of play; it is not waiting”.

- “Experimentation is safe and encouraged; you won’t lock yourself out”.

- “Failure has a price, but you always get something for it”.

- Etc.

What is critical here is not only to pick the right contract for our constraint, but to pick a contract adequate to the other contracts we already signed with our players! Conflicting or invalidating contracts are what often silently kill a game experience.

- Contract A (Identity/commitment): “Your choices are what define you; Builds are unique; Commitment creates pride”.

- Contract B (No-regret freedom): “You can never mess up; Respec is infinite; experimentation is safe”.

If we look at these 2 contracts in isolation, they are solid, positive, and have been used separately in hundreds of games. But together they invalidate each other, and using both in the same game will create constant friction. Either commitment will stop meaning anything (Builds become outfits, not identities), or players will feel betrayed if some changes are permanent (“The game told me I could experiment. Why am I punished now?”).

Below are 2 other sets of contracts. Try to find where they may collide with one another and what games still use them together:

- Contract A (Open Exploration): “Go anywhere, the world is yours to discover, and getting lost is part of the fun”.

- Contract B (Narrative Urgency): “The story is urgent and paced. You must hurry”.

- Contract A (Readability): “If you read correctly, you deserve to succeed. Clarity is fairness”.

- Contract B (Spectacle): “Surprising, chaotic sequences are where the fun is at! Screen is full, retinas are burned, outcomes get wild”.

Conflicting players’ contracts is one of the main reasons why a game feels solid on paper but doesn’t play right (churn, play-time drop, low finisher percentages…), and this will almost always happen when stacking features for their isolated perceived value without crafting them carefully for a specific game.

#3: Identify the Cost(s) you are willing to pay

Everything has a cost: either we choose it willingly, or our features will choose it for us. Asking ourselves this question early will ensure these costs are understood, chosen, and backed into our features meaningfully. As we discussed previously, there are 2 kinds of costs: the ones the devs are paying, and the ones the players are paying. The costs we are very comfortable discussing are usually the development costs: balance difficulty, QA complexity, development time, monetary costs… This is day-to-day game development.

What we are not comfortable discussing (or accepting), however, are the costs on the player side while discussing adding new features :

- Telegraphed attacks, UI preview, fixed boss phases… > Reduced surprise / predictability / gamification

- Side quests, social spaces, base building, crafting loops… > Weaker narrative urgency / diluted stakes / UI complexity

- Ranked ladders, DPS meters, leaderboards… > Optimization culture / Identity threat

- Loot drops with high variance, gatcha, procedural generation, high RNG > Win feeling dilution / Grind and maintenance bore

- Layered progression systems, high synergies, multi-currency economies, deep crafting trees > Onboarding burden, player dissociation

We cannot get away from these: we will spend simplicity to buy variety, we will spend surprise to buy fairness and clarity, we will spend freedom to buy balance…. It’s inevitable.

There will be some costs that we find very much acceptable to pay in your game, but others will be a hard no. Choosing them, instead of enduring them, ensures that our teams and game experience can afford them.

#4: Pattern Candidates

After all this prep work, it is finally time to look at some design patterns candidates! And this is where having a strong design pattern literacy will make us shine. Let’s say we are trying to solve the constraint “Need for a durable motivation loop between content drops”, a multitude of patterns could fit: daily missions, milestone-based goals, a long-term meta-progression, rotating rules (mutators, weekly), hub projects, competitive ladders… Choosing the right one will be way easier now that we know what cost we are willing to pay, and NOT pay!

Still… with many candidates, how do we choose the best one before implementing and testing it? Well, here is a useful stress-test: write down one primary contract you refuse to break and one cost ceiling you refuse to exceed, both related to your constraint at hand. Then use these as kill criteria and discriminants for your candidates. You will be surprised how many are filtered out right off the bat.

- Kill Criteria examples: “If the pattern makes power feel cosmetic, it’s out”, “If this pattern only works for players logging daily, it’s out”. Etc.

- Discriminant examples: “Which candidate produces the best attributable failure?”, “Which candidate preserves tempo the best without increasing chores?” etc.

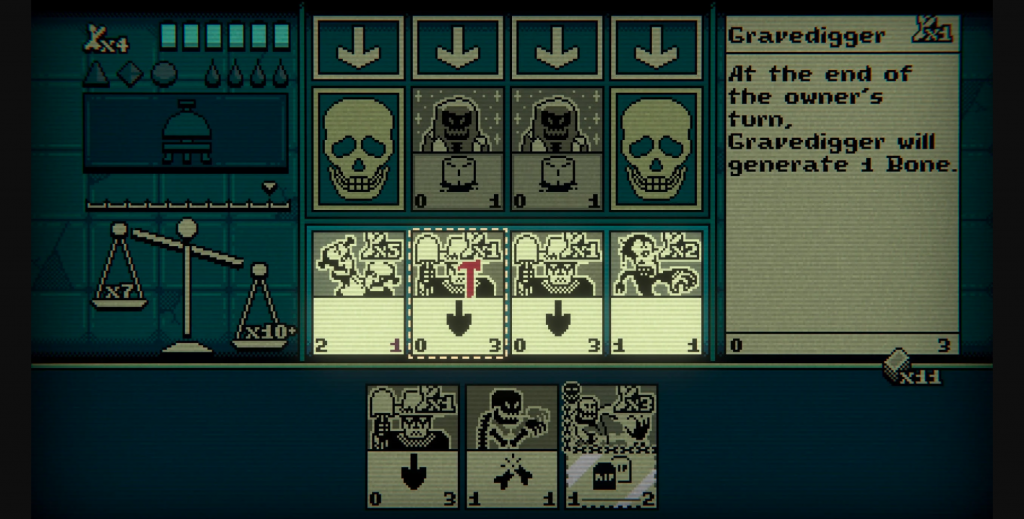

Let me take a concrete example: in the game I am currently developing, The Snackbar at the End of the World, the player must explore “the Wilds” every day to forage ingredients for their restaurant. The Wilds are split into 7 Biomes, each with their own ingredient sets that get increasingly more difficult. As we are testing it, a strong constraint appeared: late biomes must be reasonably fast to access. I can’t have players go through 30 minutes of early, easy content every run just to get to the biome they are interested in.

Multiple design patterns would fit the bill: a Hub, a shortcut system, a circular navigation between biomes, a meta-map…

In terms of costs, I have quite a few I am willing to commit to: lessened sense of adventure, stronger “gamification” feeling, loss of world cohesion… There are also costs I am NOT willing to compromise: development time (we are a small indie team), for one, but also the fact that players of every skill level must be able to access late content, and late biomes/ingredients access must feel strategic and let players showcase mastery. This last one is key as it directly collides with the constraint, and this is where we can try and find a unique solution to our problem.

In terms of discriminant, the one that mattered the most for me was “The candidate that produces the highest tempo control and strategic access”. This pushed me towards a Hub system (solution also widely used in our genre as well) but with a twist: 3 Hubs, stacked one on top of another. Each hub gives the player access to 2 to 3 biomes, but also to the next Hub. Accessing this next Hub requires the player to spend resources found in the current Hub. Coupled with a “Persistent Stash/Chest” (another design pattern), letting players bypass the requirements, I created what I believe is a great solution to my constraint, with very acceptable costs: players can rapidly access Hub #3 by being smart, strategic, and displaying mastery in the previous ones, I can easily hard gate the access to these Biomes for Narrative purpose, and even bad players can use the Stash system to quickly bypass Hubs requirements.

A Hub is a staple of the genre. But starting from the need for a Hub without understanding why would have never led me to this unique implementation (and for sure would have created much friction for me down the line).

Another interesting part of this study: it clearly points to my key tuning levers: the cost of Hubs transitions, and the Stash specifics (capacity, deposit/withdrawal limits): badly tuned, and I would either frustrate bad players (extensive grind, frustrating punishment), or dismiss the mastery component of the game if too generous.

#5: Contract-matching Metrics

Finally, we need to make sure we clearly identify the metrics that will let us confirm that our contracts are staying true, for the right reasons. If our contract is “short sessions still matter”, we may want to optimize for “% of sessions where players completed at least 1 mission”, or “DAU/Return rate”.

Be careful, metrics are easy to measure the wrong way: we can raise time in-game by adding maintenance loops and timers. We can raise retention by punishing absence. We can raise spending by adding friction and arbitrary sinks… In the example above, we can very easily skew your metrics by adding streak and FOMO systems, auto-complete missions (“log in for the day”), bribes (“Daily gift”), chore inflations, etc.

Players feel the difference between “the game wants me to…” and “the game forces me to…”. If our patterns drift our game from play device to obligation ones, we’ll get the numbers until we don’t.

A Final Warning: Player Contracts are Everything

A mistake I often see in production, and the reason I’m insisting so much on the “Player Contracts” lens, is the mismatch between what designers are trying to do and how players perceive it. For example:

- Systemic intent: “We need to prevent DPS spikes from trivializing encounters.

- Design pattern: Enemy scaling to player level.

- Player perception: “Progress is fake, getting stronger doesn’t change anything”.

- Previously Established Contract break: “Grinding makes me powerful”.

This design pattern is a classic one, and has worked in many other games, but in this hypothetical scenario, it creates a mismatch between the contract we previously made with our players and what the game is actually doing. A lot of other design patterns could fit the bill here: partial scaling, player-driven difficulty paths, narrative difficulty raising (ex: Hollow Knight’s corrupted crossroads), etc.

Upholding player contracts is one of the most important responsibilities of a Game Designer, in my opinion. And it’s oh-so-easy to forget about them… Sometimes, they are contracts we signed with players early on that can drift across the game (ex: enemies abandoning readability later on for the sake of “difficulty”), sometimes it’s contracts our game genre (or the genre we are advertising) signed for us that we aren’t respecting (ex: roguelites “failure is learning and progressing, runs are short, variety is expected” or looters “progress is constant and persistent, variance is where the fun is at, optimization is social”). Whatever it is, we MUST do our best to ensure they do not contradict each other, and they stay true throughout the experience.

“But wait a little bit… Sometimes, purposely breaking contracts or having them collide is what creates the best kind of content! An obfuscated objective, an intentionally impossible-to-read boss, a system that flips progression on its head! You are being way too strict!”

Ahah, now we talk! There are indeed moments where bending the rules leads to killer results. You could consider colliding contracts by segmentation (story mission vs. open world, for example), staging (the contract changes over time, and is properly telegraphed to players), or simply as big one-offs for dramatic effects! Here is where our experience as game designers will shine!

Conclusion

Treating design patterns like magical recipes will only make us curators of other designers’ solutions. Instead, approaching them like the potential answers to recurring constraints will make us the authors of our own trade-offs.

Study your game’s unique constraints, treat player contracts as your game experience’s sacred foundation, choose the costs you can afford (and the ones you WON’T afford), and only then start to consider solutions. Sometimes, it will look like the textbook design pattern; more often than not, it won’t. As long as you can explain it, tune it, and when needed, reject it.

A design pattern you can’t explain is a pattern you can’t control.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please consider supporting GDKeys on Patreon. It helps keep this place free of ads and paywalls, ensures we can keep delivering high-quality content, and gives you access to our private Discord where designers worldwide gather to discuss design and help each other on their projects.

1 Pingback