If you have been around this blog long enough, you may have noticed that I’m quite fond of the history of games. There is just so much for us to learn from it: how games have been birthed thanks to technological advancements, available resources, or societal organizations, spread through continents following trade routes, evolved with human groups and societies…

Ultimately, the history of games is a very human one. And though games transformed and adapted at an extremely fast pace through the ages, humans traits, psychology, and characteristics stayed pretty constant. Which prompt a question: are the game from the past still holding up by today’s standards?

Of course, we can already answer pretty well this question as we have games like Go, Chess, Dice, or Mahjong that are still considered masterpieces today. But what if we could go even further back in time, back to the earliest board game in existence for which we still know the rules (or at least one set of rules, but we will get to that), and look at its design with our modern eyes?

The Royal Game of Ur

Let’s start with a bit of history, to understand how we managed to get access to this fabulous piece of game design.

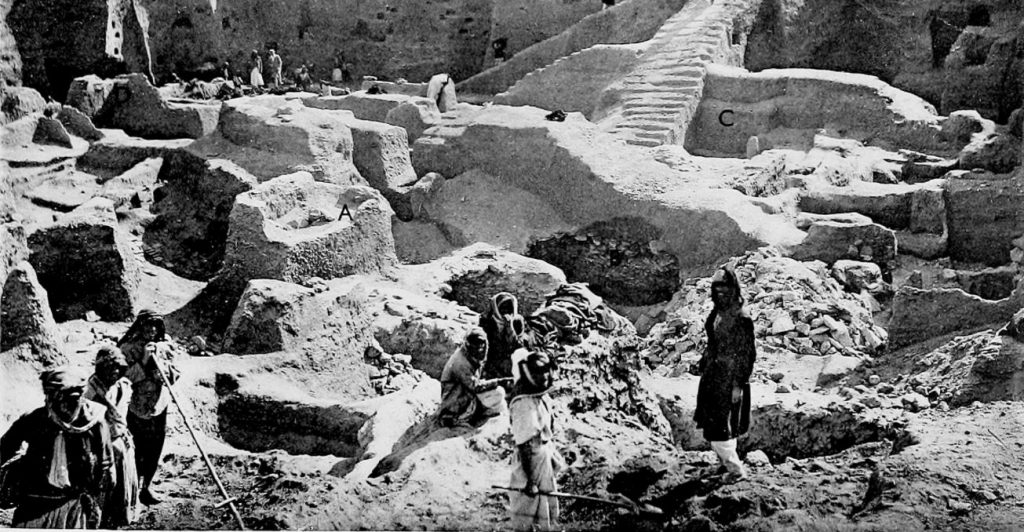

We are in 1922. Sir Leonard Wooley, then archeologist for the British Museum, is excavating the Royal Cemetery at Tell el-Muqayyar (southern Irak today) on the site of a Sumerian city, Ur, founded almost 6000 years ago.

Among his discoveries figures not one, but five artifacts resembling what seems to be an unknown board game, dated back to 2600BC. These boards are of beautiful craftsmanship: intricate patterns, obvious symmetry, precious stones like lapis lazuli, and red limestone inlaid, adorned of unknown symbols which, though not saying much, could testify of the importance they held. Being the first appearance of this unusual game, it took the name of the place of its discovery and became known as The Royal Game of Ur.

These boards were sent to the British Museum, which still holds them on display today, and were pretty much forgotten about, game design-wise.

But then new boards started to appear in other excavations: Iran, Syria, Egypt, Lebanon, Sri Lanka, Cyprus, Crete… Not only was this game played across the entire Mesopotamia and beyond, but it was also crossing the ages: these boards proved that the game, in its form, has been played at least until late antiquity. The Royal Game of Ur is a game that has been played, with minimal transformation, for at least 4000 years! To put things in perspective, Ramesses, and Nefertari, would they have been playing it, would have already considered this game a relic of the past, something that has always been.

But did they even play it? You bet they did!

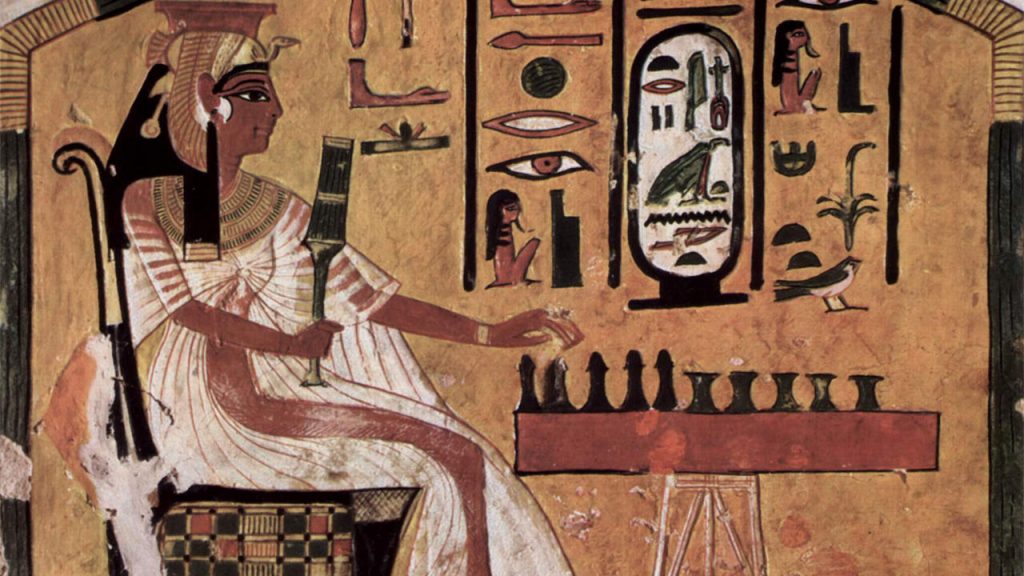

The picture above is representing a wall painting from the tomb of Queen Nefertari, showing her playing Senet against an invisible enemy.

Senet? Another game? Well… Kind of. The game of Senet is a game belonging to the same family of board games, the Tabla games (containing games like the Backgammon, or Hounds and Jackals), and that bears strong similarities with The Royal Game of Ur: 3 rows of squares, 2 players, 2 sets of pieces, marked sticks for dice… Actually, they are so resemblant that we discovered multiple game boxes bearing the Senet board on one side, and the Royal Game of Ur on the other, with a central drawer to hold the game pieces of both games.

Think about it: an Egyptian Queen was not only playing but has been buried with boards of the game you are going to learn to play today. If this isn’t amazing you, I don’t know what will!

But we are now reaching the point in our story where the real issue lies: finding games’ artifacts is one thing, reconstructing how these games were played is a whole other problem!

Think about it… When games have been played for thousands of years, they become part of the common knowledge: everybody knows how to play them. Having someone wanting to go through the long process of carving a clay tablet to record rules that will be useless in the present time is highly unlikely. This is why games like Senet or Hounds and Jackals, though determinant in the history of games have unknown rules today (or a lot of guesswork based on the ancestry of these games and game specificities like board and pieces).

But, in the case of The Royal Game of Ur, something significant happened.

Historically, when games have been ingrained into society for so long, they tend to permeate every aspect of said society, to the point that they infiltrate religion, and beliefs. When this happens, usually these games get a regain of activity as well as significant evolutions in a very short period of time, few dozens of years. And this is the kind of event that is worth documenting: how does a game is now of important significance into predicting the future, or guiding a soul through the Duat, or conversing with dead relatives… And this is exactly what happened with The Royal Game of Ur!

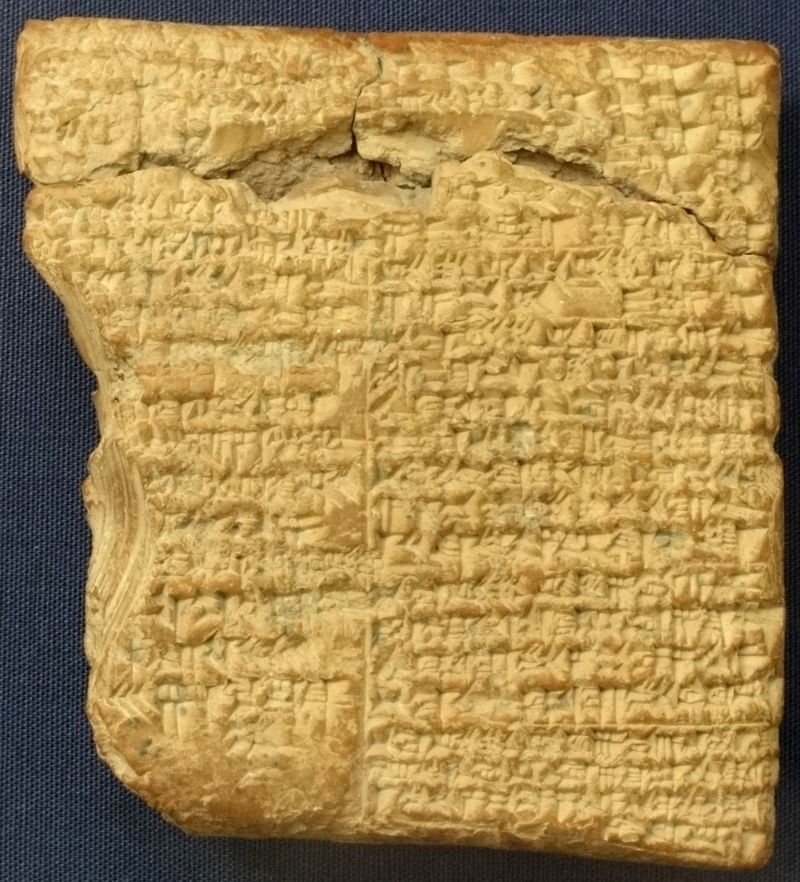

In the early 1980s, Irvin Finkel, a curator at the Same British Museum holding the game boards artifacts, was translating clay tablets unearthed in the ruins of Babylon when this one appeared:

This tablet was describing the spiritual significance and omens linked to the different rules and cells of an unnamed board game (predictions like “You will draw fine beer” or “You will become powerful like a lion”). It was also describing some advanced rules allowing betting. Not only the rules were very descriptive, but the diagram of the peculiar shape of the board of the game was engraved on the back of the tablet. No doubt remained: this was the rules of The Royal Game of Ur!

You are looking at the oldest rule book in existence, a clay tablet that allowed Finkel to piece together how the game was played (or at least the variation at this moment in time). The mystical aspect of the game, as well as the significance of its patterns and recurrence of the number 5, is still lost in time, but at least now we can play it.

Game Rules

The Royal Game of Ur is a 2 players race game that is an ancestor of the Tabla games like Backgammon. It is still debated either Backgammon evolved or replaced this game over the ages as a less luck-based, thus considered superior, game.

Like other Tabla games, the rules are pretty straightforward: launch dice (or an equivalent of dice) to find out how many squares you can move your pieces, and manage to have all your pieces enter, travel through, and exit the board before your opponent does it.

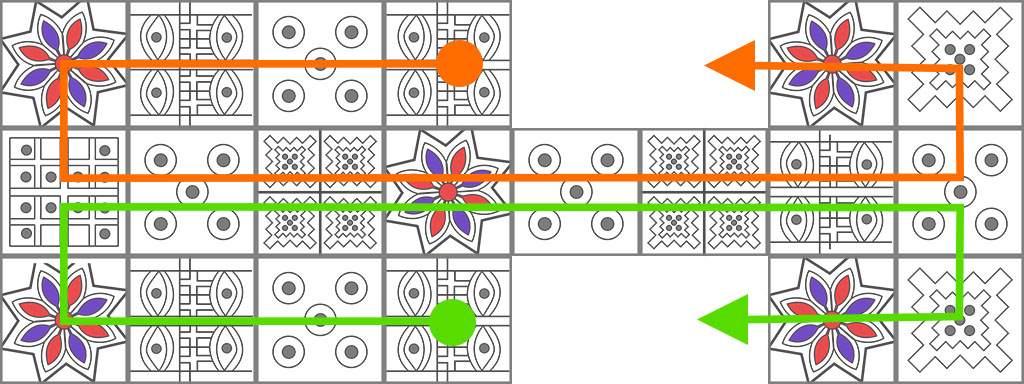

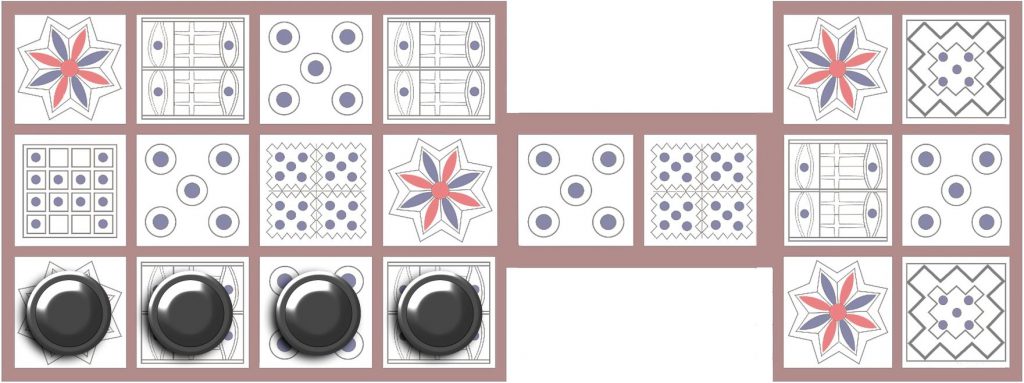

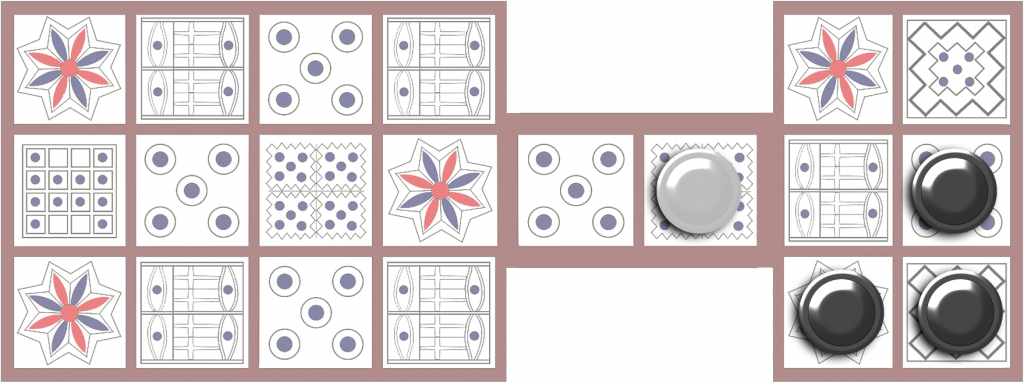

The board is organized as shown below:

And here are the rules:

- Each player own 7 pieces.

- Each piece must first enter the board, then travel all the way until the end of the path, and finally exit by rolling the exact number to jump out the board (last cell +1).

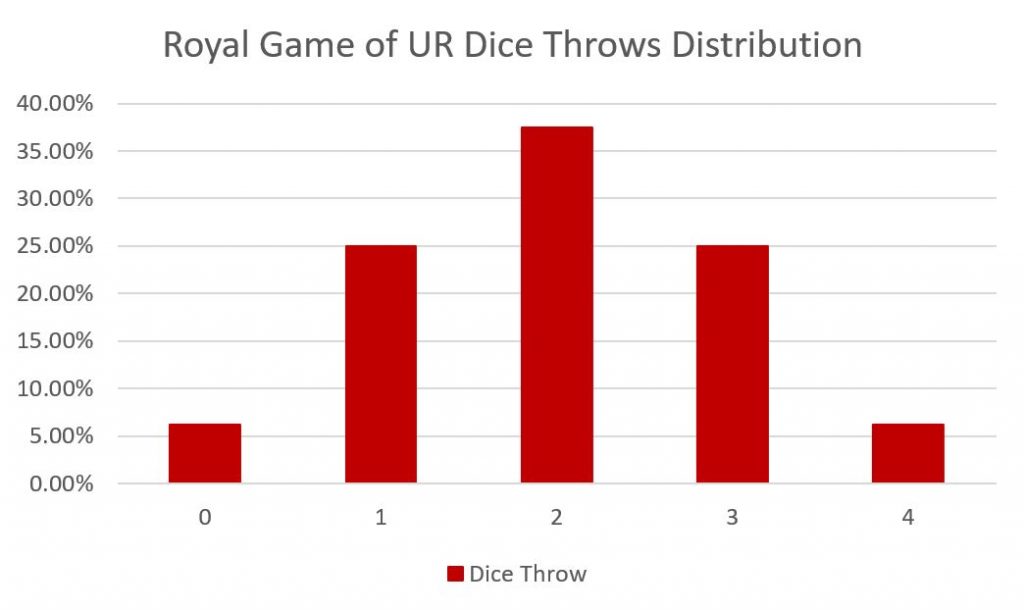

- Players will throw 4 dice that can result either in a “0” or a “1”. The original version uses 4 sided dice that have 2 points painted in black and 2 in white.

- Once the dice are thrown, a number between 0 and 4 will be obtained. This number can be used to move any piece by this exact number. Subdivizing the number isn’t possible. Example: I roll a 3, I could bring a new piece on the table to the third position, advance any one piece by 3 squares, or make a piece exit the board if the third move make it exit the board. If no move is possible, then the turn is lost. Also, moving a piece is an obligation if possible, which shouldn’t be a surprise for Backgammon players.

- The first 4 squares, and the last 2, are safe squares for both players (only them can have pieces there) but the 8 central ones, the Combat ones, are shared between players, thus putting pieces at risk.

- If a player move one of their pieces on a square already occupied by one of their opponent’s piece, the enemy piece is “eaten” and goes back at the start, outside the board.

- The 5 Rosace squares are Jokers: landing a piece on one gives an extra turn to the player, but that’s not all: a piece sitting on a Rosace cannot be eaten (applicable, of course, only to the center Rosace, making it effectively the best cell of the game).

And… that’s pretty much it! If you still have difficulties picturing the game (as it is usual with written rules), I very much invite you to watch the following video, featuring Tom Scott and Irving Finkel Himself, who not only rediscovered the game but is also an amazing entertainer and pedagogue!

Design Study

Now that we finally finished presenting the game, its history, and its rules, it’s time to ask ourselves a pretty important question: is this game any good?

On one side, it has been played for 4500 years, which should be a pretty good indication that it is robust and well crafted, but let’s prove it by looking more closely at its different components, as well as the different players’ strategies this game creates.

Randomness & Control Over Luck

The Royal Game of Ur has a strong Randomness component. Players will throw dice at each turn to determine by how much, and if, they can move. The existence of Luck, as discussed in The Components of Timeless Social Games, is an excellent way to bring uncertainty and exciting situations in a game: it makes it feel more approachable to new players, it evens the field in terms of skills required, but also creates replayability.

Though the game is very Luck-based (estimated 60/40, possibly one of the reasons why Backgammon took over) it is countered by the dice values and design. The game is played with 4 pyramidal dice. Each of them can result in a “1” if the upper tip is white, or a “0” if not. And this is an excellent design!

The game could have used a single 4-sided die, ranging from 1 to 4, with equal chances to land on any possibility. But the use of 4 dice brings key advantages: First, players can throw a “0”, which would make them effectively lose their turn and potentially shift the course of a game. But most interestingly, it gives each possible roll very different odds.

Let’s study this breakdown:

- 0 and 4 are the rarest roll, each siting at 1/16 chance to come out. This makes epic fails, and epic wins, rare and meaningful.

- 2 will be the roll that will come out the most, at 6/16 chances. This allows strategies to emerge: having a piece 2 squares behind an opponent’s one will apply pressure and force them to move or risk getting eaten.

- 1 and 3, at 4/16 chances bring enough range to create a fresh, surprising, and evolving gameplay.

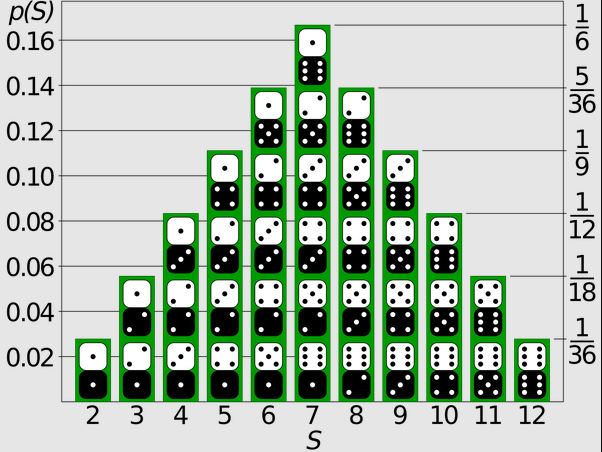

The choice of dice (number, face values) is extremely important in any game involving luck as it will affect deeply the amount of strategy and control players will have. The fact that Monopoly is using two 6-sided dice is creating odds that tremendously favor certain squares of the board (and arguably allows to predict the winner after 2 turns around the board, but this is for another article):

So, luck (and its control) wise, the game is holding pretty well so far! It is also worth noting that Rosace squares are placed every 4 tiles on the board, rewarding epic “4” rolls with another roll right away. To add to it, rolling twice a 4 will place one of your new pieces directly on the center Rosace.

This gives us the perfect transition to talk about the board design itself and the different player’s strategies at play.

Players’ Strategies

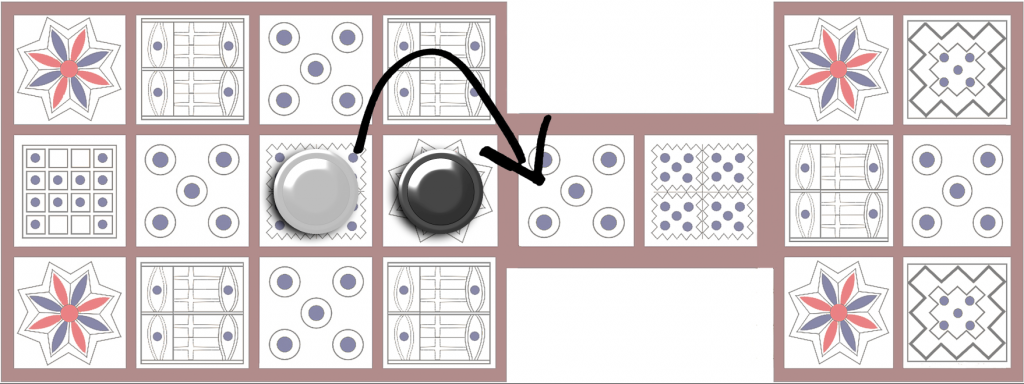

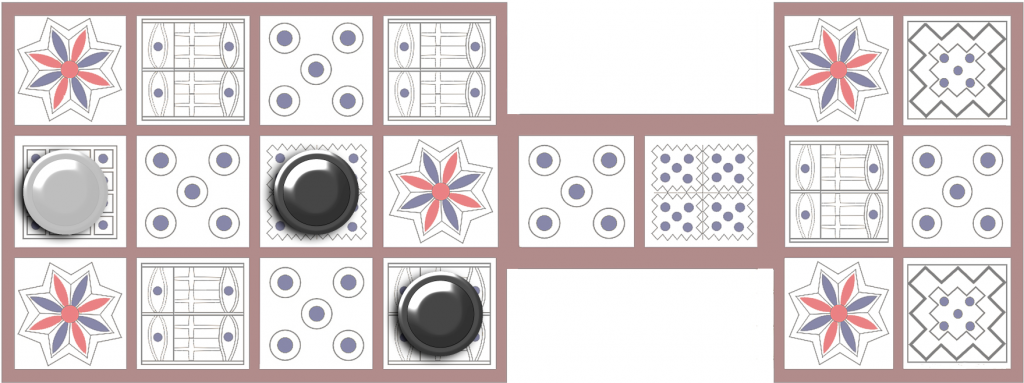

The fact that not every square is a “combat” square (compared to Backgammon for example) allows for some neat strategies to appear.

Imagine the situation depicted above: Black has 4 pieces on each starting squares. Doing so will make the first combat square a dead zone (any roll but a “0” will let Black take it), and globally prevent White to even enter the battlefield without a seriously high roll. On the other hand, this situation also closes a lot of doors for Black to move, and the next roll will force a move in the combat corridor.

Though the first squares of the corridor are the most dangerous, they are also the cheapest to recover from: losing a piece at the end of it could drastically change the course of a game and send you back multiple rolls.

With this in mind, let’s look at the central Rosace, the most powerful square of the board: not only a piece there cannot be captured (and can then stay here for an extended period of time), it also forces the opponent to jump over it to progress, putting this piece in jeopardy of being eaten far in the corridor.

Pro-tip: if you have one of your pieces on this Rosace, leave it here until the moment to unleash hell comes.

Finally, the 2 safe spots at the end of the board seem like a perfectly good place to stay while fighting other fronts. This statement is true up to the point your pieces there will block the ones progressing through the combat corridor: nothing is more frustrating than losing a piece at the end of the corridor because your other pieces clogged up the exit safe spaces.

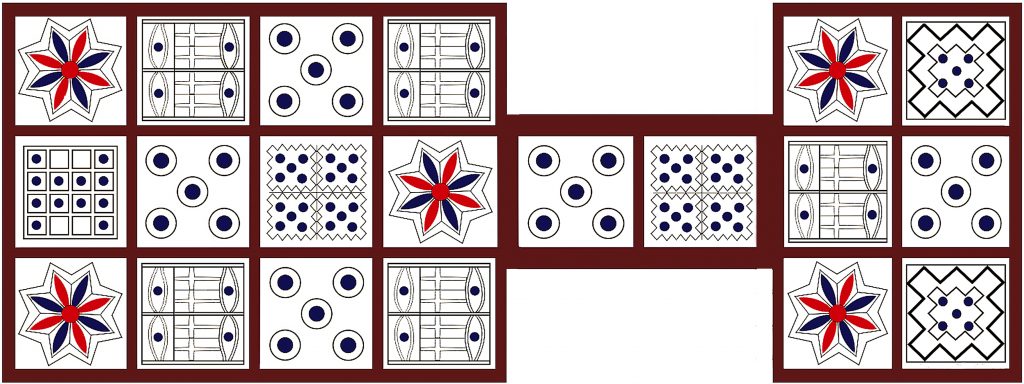

This following situation, for example, would be a very unfortunate one to find yourself into should you play Black, can you now see why?

All in all, the strategical layer of the game is deep, full of micro-decisions and risk/loss-aversion moments.

Catch-up Mechanics

Another surprise is how well the game develops its own catch-up mechanics and makes every match a pretty tight and thrilling one.

As discussed previously, the eating mechanic combined with the exit squares getting crowded is putting pushy players at risk: the more pieces they push at once on the board without properly getting them out, the more a player falling behind has a chance to eat a piece well advanced on the board, which would send them back several rolls. These micro catch-up moments are actually happenning multiple times throughout a game and equalize constantly the game field in some pretty dramatic fashion.

But now let’s imagine that a player plays very well against you, and gets very lucky on top of that: a “6 to 3” pieces out so far, a huge advantage.

In this case, the leading player will have only 1 piece left to win the game, compared to 4 for you. Sounds dire, but it is actually not that bad: having a single piece left means that your opponent is at the mercy of Lady Luck, without options anymore (and obligated to make a move if possible). On your side? You have 4 pieces to spread around the board to prevent any possible progress.

These catch-up systems generate very tight games, always leaving the possibility for both players to prevail at the end (and I’ve had some fabulous comebacks!). At the same time, though luck plays a very important role in deciding the winner, the strategic aspect of the game allows the best player to win most of the time.

Regional Variants & Extra Rules

An interesting aspect of these social games are the regional variants they generate, and how it affects the meta of the game. Though we unfortunately don’t know much about the game, we can at least trace back one variant thanks to another clay tablet (destroyed during WWII but some pictures survived).

This variant, a betting one, was adding few extra rules to the original game:

- Skipping a Rosace square forces a player to put a coin in the pot.

- Landing on a Rosace square allows a player to take a coin from the pot.

- Winning the game awards the winning player the rest of the pot.

These extra rules add another layer of strategy, planning, and risk to the game. Say your are playing black, find yourself in the below situation and roll a 2:

Do you skip the central Rosace, put a coin in the pot, but play safe with your central piece? Or do you instead move the other piece, hoping for a “1” next turn, while putting yourself at risk with a white threatening you? Decisions, decisions…

Try the Game Yourself

If you read this article until here, you probably want to try the game yourself now! And lucky you, there are plenty of options for you to do so!

- You can purchase the official replica on the website of the British Museum. The pricey option, but quite a conversation starter to have on your coffee table isn’t it?

- You can purchase cheaper replicas from Amazon.

- You can play the game on Tabletop Simulator.

- Or you can simply print the below picture on A4 paper and improvise the game pieces and dice!

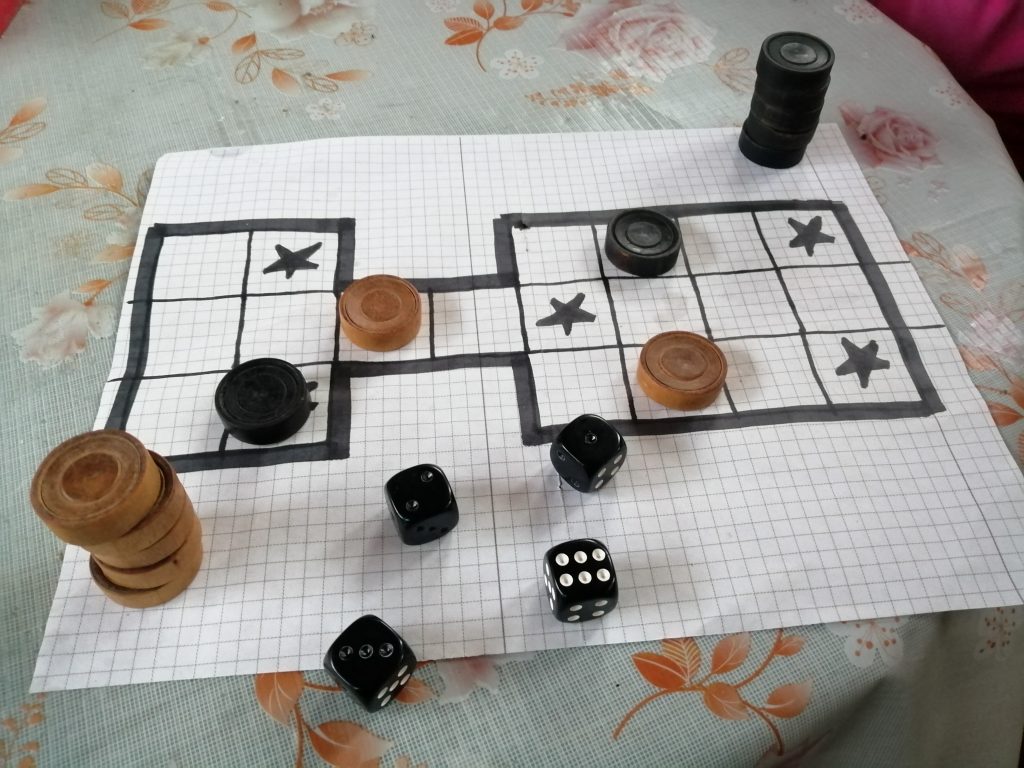

If you want to give it a quick try with family & friends, just have a look at my homemade version below (that I still play today!):

- Hand-drawn board, marking the Rosaces of course

- 7 white and 7 black pieces taken from a checker game

- 4 classic 6-sided dice, with their 1, 2, and 3 painted black with a marker (counting for a “0”) and 4, 5, and 6 left white (counting for a “1”). The roll on the picture above is thus a 1.

Not only this works perfectly, but it is also more pleasant to manipulate cubic dice instead of trying to pick up 4-sided ones with greasy barbecue hands (I suspect Sumerians were having claws instead of hands).

Conclusion

Well… My personal conclusion is that this is a pretty damn good game! And if you read my previous article, The Components of Timeless Social Games, you may have noticed that this game ticks pretty much every box of what makes a solid social game.

It may seem logical, but it’s quite fascinating to me that a game almost 5000 years old, evolving and branching through the ages and geographical spread, managed to naturally reach a point where its game design old strong from today’s standpoint. We are having jokers, double-turns bonuses, skip-turn maluses, catch-up mechanics, uneven odds, and strategical planning…

To me, this is proof that trusting players and communities to appropriate a game and make it evolve will transform it into a better version of itself, iteration after iteration, and why so many Game Design breakthroughs came from the work of modders. Game design is a very human craft, and it seems that the evolution theory and the survival of the fittest apply themselves in this domain as well!

Do you want to get regular quality articles on Game Design and join an awesome community of devs and designers on our private Discord to discuss design, learn, and review each other’s games? Then consider supporting GDKeys:

Seems like leaving the center pip on the one face, the three face, and the five face the original color and blacking out all the other pips would look better.

I am a long time collector of old or regional board games(Mancala, Nine Mens Morris, etc.) that I have used in my classrooms over the years. Just this last year, I came across a reference to The Royal Game of Ur and I love it!! Now that I am a private tutor I travel house to house, so I made my board on a placemat that I can easily transport. My students enjoy the game as well and it blows their minds that it is so old.