As any game designer knows too well, the biggest mystery in our design equations will always remain our players themselves. Their variance and diversity in aspects like backgrounds, needs, desires, skills, motivations, abilities, and willpower will always lead to unexpected results and push our designs in wild places.

This is why game developers have turned themselves towards anthropology, psychology, and other behavioral sciences in order to try and mitigate these facets and better understand players.

There are plenty of discussions I would like to have with you on this blog and as many articles that I want to write on the specifics of this topic and their applications in game design and experience design. But I realized that, though it may be already well known by some of you, many of our readers here never got to really learn about this side of game design, making this article an important step towards deeper ones.

The players’ aspect we are going to discuss today is not only one that every game must tackle, but it is also probably the most applicable one and could be summed up with this question:

What motivates players to engage in a video game and continue playing it?

Game designers have been asking themselves this critical question since the creation of our medium and, in the absence of magic formula, one can but assume that the answer is more complicated than it looks.

For a long time, extrinsic rewards have been the one and only answer: high-scores, extra balls in pinball (and extra-lives in games), in-game money or rare items, praises and titles… The method is tried and trusted. Carrot and stick, reward and punishment, has historically been a very effective method of inducing specific human behaviors: from schools and governments to the Ming dynasty or Stalin’s Soviet Union, history is full of examples of this rather direct form of motivation. It also continues to be a very actual approach: its central place in the continuous debate around public education being a clear proof of it.

A famous application of the Carrot and Stick approach that easily comes to mind is Skinner Boxes, a testing apparatus invented by the eponymous behaviorism psychologist, that became instrumental in the success and addictions behind everything from casino to free-to-play games or fidelity programs.

This proven behavioral approach is entirely driven by forces outside of one’s control. In video game terms, this means that players engage with a game’s activity solely for the reward that is promised (or the punishment that may occur should he refuse): craft hundreds of daggers for mastery in crafting, replay a raid over and over for a chance to receive a legendary item, complete a specific side-quest to unlock an alternative ending… Examples are so numerous that you could write pages of them yourself.

But now let’s bring another side of this topic. Behavioral psychology has been studying human motivations for much longer than video games exist, and figured out for already quite some time that extrinsic motivations wear off pretty fast compared to intrinsic ones. How many games have you stopped playing because it felt too repetitive? Or because you lost “purpose”? How many systemic events are you willing to play in the same area before feeling that it isn’t worth it anymore? How many camps will you clear on the map before it all merges into the same brainless gaming blur? The lack of intrinsic motivation is not immediately apparent. It creeps in taking different forms: frustration, boredom, reluctance to engage until, finally, the player simply stops playing the game.

Players will engage much more easily in a game for the promise of extrinsic rewards but will keep playing for the intrinsic ones that supplement them.

In short, intrinsic motivations are all the intangible motivations initiated from within an individual: the knowledge of doing the right thing, the satisfaction of personal growth, the joy of socializing with other players, the pleasure of creating something or expressing yourself…

Combining both types of rewards and motivations, the intrinsic and the extrinsic ones, creates for all types of players extremely engaging, long-lasting experiences, if done properly. I invite you to check the following GTMK video that perfectly explains how extrinsic and intrinsic motivations influence each-other, sometimes to a very negative degree: The Psychological Trick That Can Make Rewards Backfire.

Intrinsic motivations are tapping into the core of what drives us, humans. They are the most impactful, yet very often forgotten in favor of easy, shiny tangible rewards. And yet, in them lies the secret of our games engagement and retention. But this isn’t all, intrinsic motivations do not need external activator to be answered:

Extrinsic rewards dry up.

Intrinsic rewards feed themselves.

A player, driven by extrinsic rewards, will drop from a game the moment this flow stops, forcing developers to always add more challenges and more rewards to keep their players in the game, while intrinsic rewards are player constructs, and virtually infinite.

More design, less production time, more engaged players, better retention.

But how can we quantify, or find actionable points, on something so personal and core to each and every human being? What would make for a universal game design model that could help us shape and refine our experiences to be more human-driven?

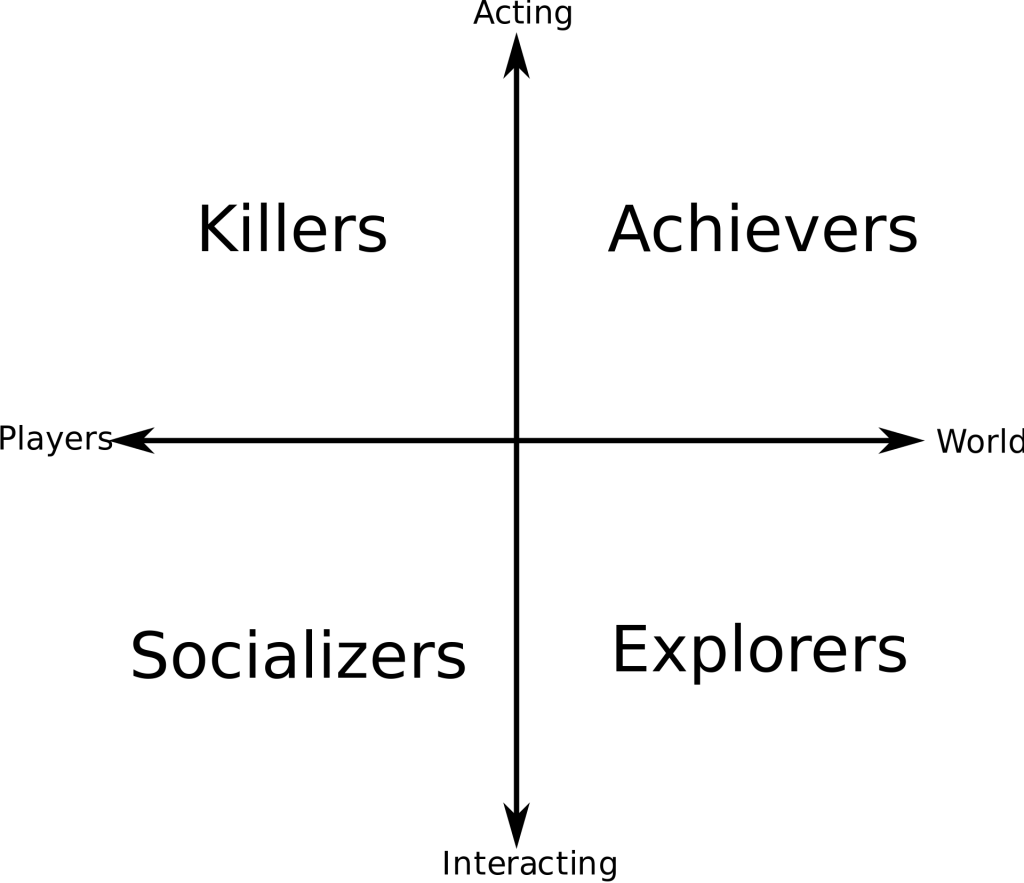

The first model that got international traction in the video game industry was without a doubt the Bartle Players’ Taxonomy in the ’90s that you probably are already familiar with.

This player’s categorization got everything right to become widely known: a model created directly from and for video games, easily scalable, and applicable. For quite some time this model was the reference and definitely helped introduce video game developers to cognitive psychology. The promise was simple: create systems answering each and every one of these quadrants and you get yourself an engaging game tailored for every player.

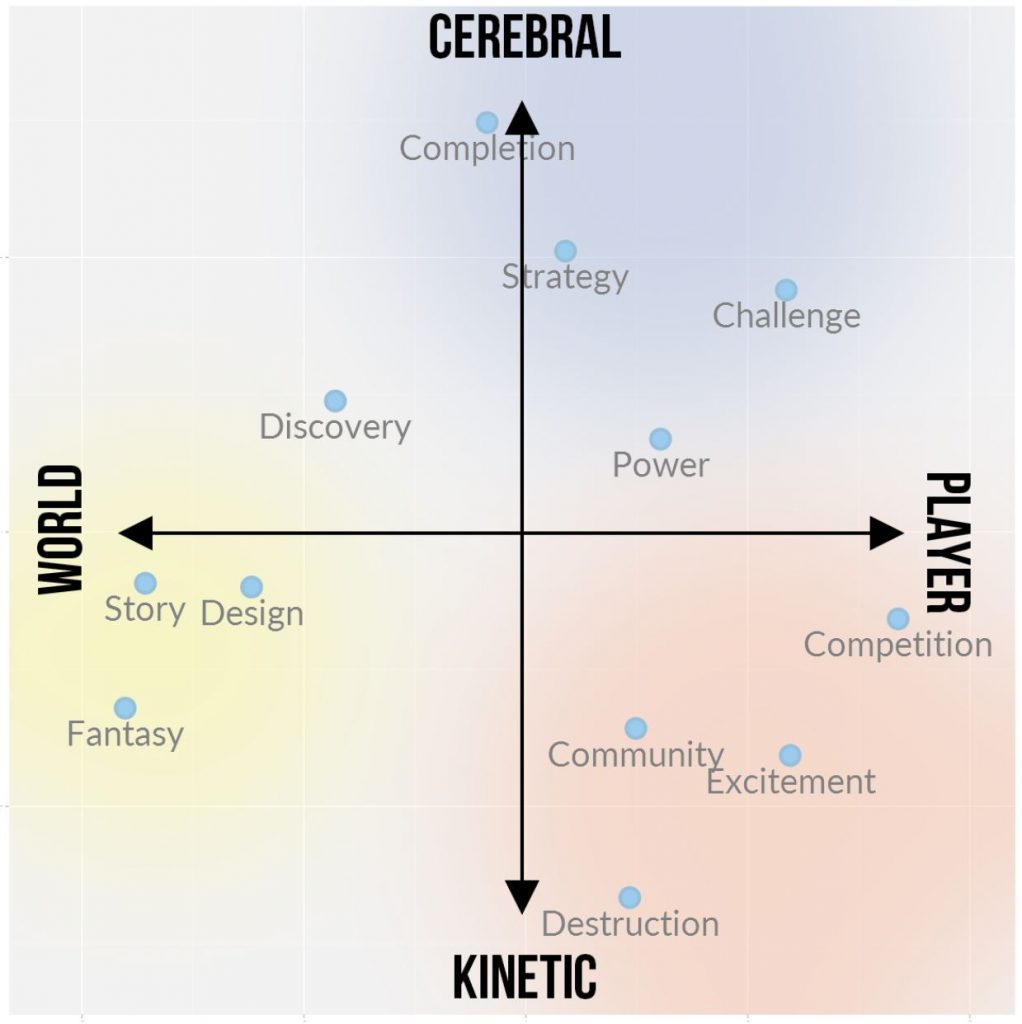

From Bartle’s work, a multitude of approaches emerged to try and refine these players’ core motivations, like the Gamer Motivation Model from Quantic Foundry that proposed a more granular approach to Bartle’s model:

But this approach came with an important issue: it was never meant to be widely used. Bartle created this model after designing MUD, the ancestor of the modern MMORPGs. It is an approach that started from the components of a very specific kind of game, and defined players types based on it. Most games today won’t ever be able to fit in these categories, and will most likely focus on few specific parts of it.

The industry naturally moved away from this model. But this doesn’t make it obsolete. This model is still relevant for every MMORPG around (though now they tend to find their identity and audience by strongly emphasizing one of these quadrants), but also potentially for any other game. By mapping all your features on this grid, it may make you discover lacks in your game, or simply help you visualize the players you are developing your game for, or understand your own game.

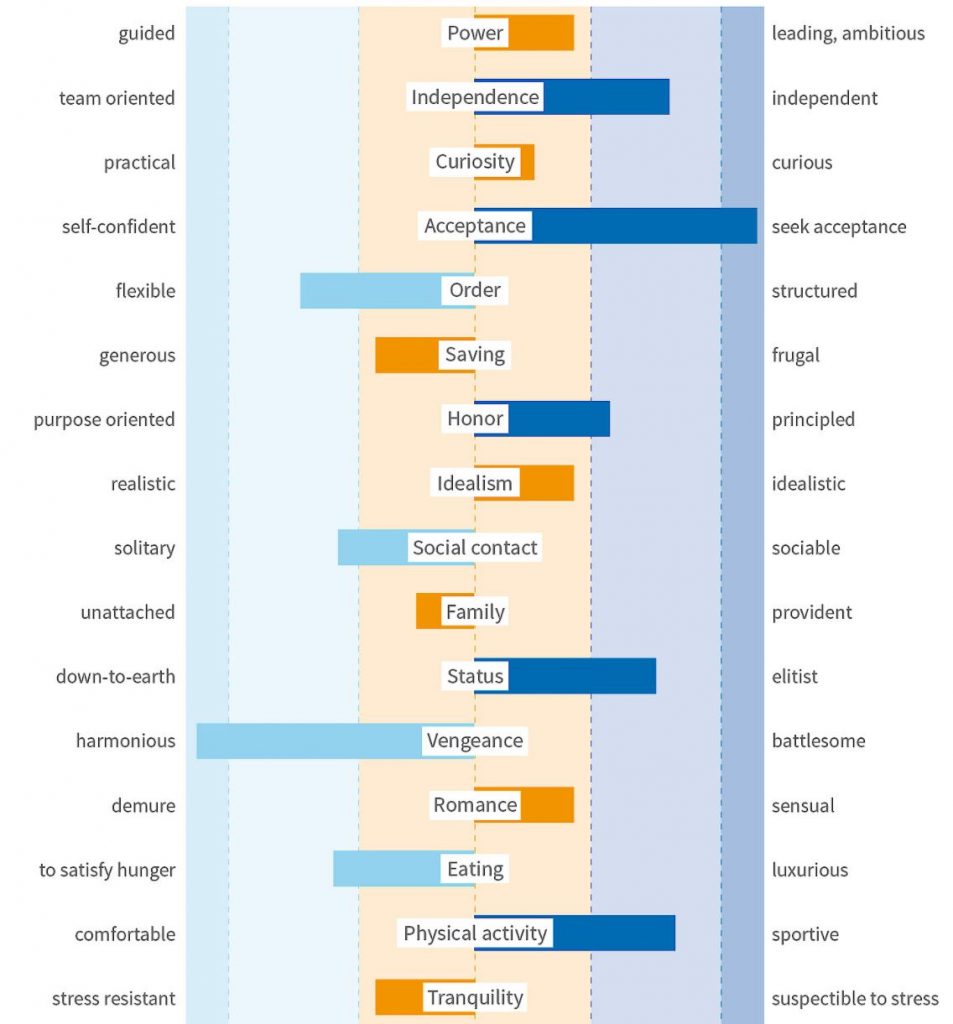

Now, this model is far from being the only one around. Another extremely popular model is the Reiss Motivation Profile, developed by Steven Reiss, a highly influential behavioral psychologist, in the late ’90s.

His model breaks down an individual needs into 16 key-variables. It has been widely spread across all kinds of domains and has a proven record of being an accurate representation of one’s underlying motivations. Indeed, human motivations are created from a wide range of places:

Motivations are driven by underlying factors, such as needs, desires, and values.

It then made a lot of sense for the video game industry to try and use this model too. But several issues made it very complicated to exploit:

- These 16 items can be very difficult to translate in terms of video game motivations and systems. How do you address a human need for physical activity or family?

- As they depict very precisely your players’ needs, every game would need substantial research done in averaging your players into key personas.

- Finally, probably the biggest turn-off: the methodology is proprietary and isn’t actionable without the company behind it.

As a result, the industry never really adopted this model, and preferred another one, way more accessible, applicable and streamlined.

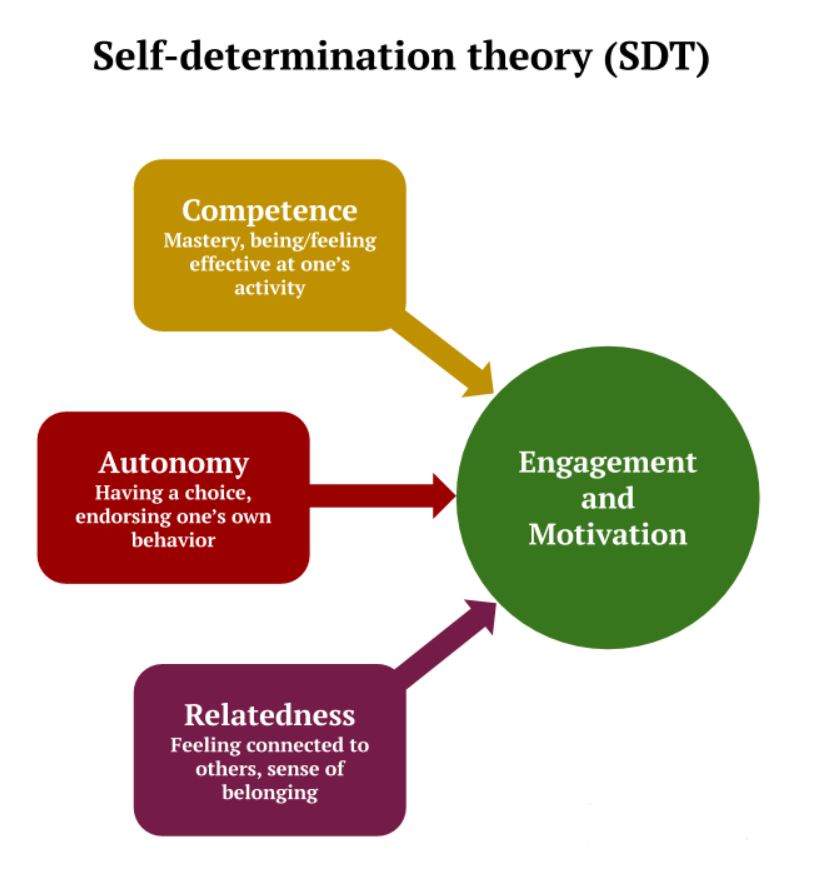

Enters, the Self-Determination Theory.

This macro theory appeared in the ’80s and is the direct result of the different researches studying extrinsic and intrinsic motivations and their impact on self-motivation and self-determination. The good thing is, it plays only with 3 attributes: Competence, Autonomy, and Relatedness. This theory state that these attributes are core human needs that are innate, universal, and leading to motivation, growth, and purpose. It is described as follow:

This model has also been used extensively by many domains and isn’t by all mean a video games specific approach. It’s a very human-centered one that could be applied to video games.

And this is exactly what the folks at Immersyve did. They took this model, and applied it to our industry, creating the PENS, for Player Experience of Need Satisfaction, an approach based on the study of thousands of players and the impact of these items on their engagement and retention. If you want to go deeper in this subject, they wrote a book on it: Glued to Games: How Video Games Draw Us In and Hold Us Spellbound.

Let’s break these items down:

Competence

This core player need is about self-efficiency, mastery, progress, and growth, and is closely related to the concept and theories of challenge. The whole “Easy to learn, hard to master” fits right in this category. The concept of flow too.

This critical need could be expressed as giving players the optimal challenge and letting them express their mastery. But this statement is only the tip of the iceberg, as it encompasses everything around it: the depth of the tools and system given to players, the tokens of progression, the acknowledgment of said mastery, and their associated rewards.

Humans are drawn to growth and feed on conquest, and it is such evidence that most games are using Competence as their main driver without even realizing it.

Autonomy

This one item starts to be more difficult to grasp and apply in games. It is defined as the choices our players have. Humans have the need to express themselves, and their behavior is comprised of said choices. The more they have, the better.

But there is a danger here. How about letting you choose between 2 paths? Or being good or evil to develop a story-line? Does this count as a strong Autonomy?

The answer is no. These choices have been forced upon the player, they are controlled and controlling. This is all the subtlety of this item: true choices aren’t imposed on players. True choices are truly one’s own, they are self-initiated.

In short, it is less about giving player choices, and more about enabling the player to make his own. This leads to very interesting challenges that the industry is still trying to answer: what will enable more Autonomy in the customization of a character? The amount and variety of visual items available? Its background or development? The unicity and representation of the player? Or another: do open-worlds and organic storylines make for better Autonomy than directive, linear ones?

Relatedness

Finally, here is the most complicated item to grasp. In the Self-Determination Theory, its description is clear. It is described as the “will to interact with, be connected to, and experience caring for others”. So in all logic, its application to social-heavy games is pretty straightforward: it is about enabling the player to engage in deep and fulfilling social interactions, a critical human need. Clans and group constructs, unicity, sense of belonging… We all know how strong these motivations can be.

But does that mean that single-player games cannot answer this need? Far from it, but it comes with nuances…

Relatedness is the need to care, and be cared for, the feeling that “What I do matters” and “I matter”. That you do not only grow yourself but grow as a group, a community, a world.

Impacting the game world, leaving traces, connecting and bonding with NPCs, bending story-lines… All these examples are directly answering this item.

Also, in the current age of sharing and streaming, of “always connected games”, we now have a lot more possibilities to allow players to share their personal experiences with other people (compared to the simple high-scores a few years ago). It’s connecting our players’ experience to something bigger than them.

This model is actually the one I am referring to the most these days. It is simple, actionable, and bring a human-centered approach to user experience and game design.

As Paula Neves, product manager at Square Enix, puts it: “by focusing on the 3 basic psychological needs that the SDT proposes, game developers would be dealing with the psychological experiences that form the building blocks of fun and not on fun itself”. Fun is but an intangible outcome.

This introduction to players’ motivation, needs, and the reward paradigm, is by no means exhaustive. The topic is in constant evolution and I’m sure we will have a lot more to discuss together.

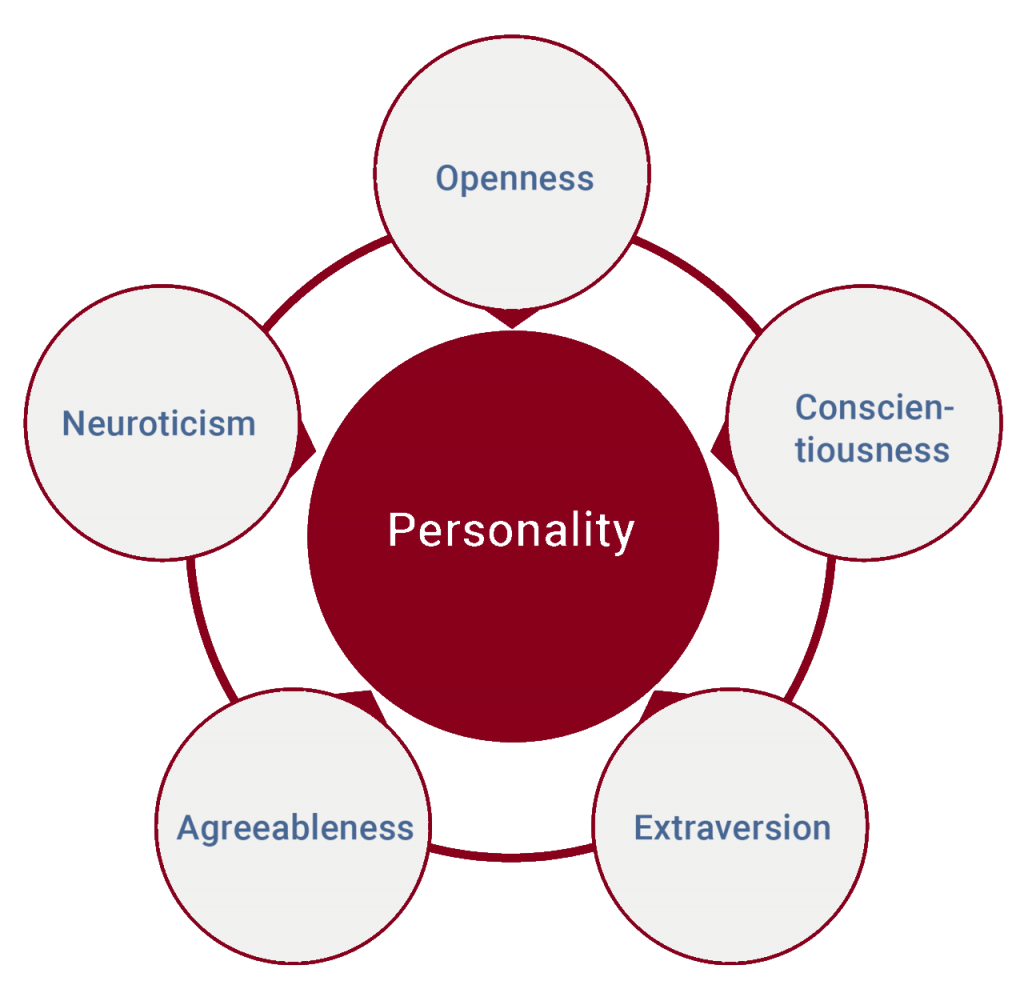

If you want to continue to dig more by yourself in the meantime, I’d highly recommend you to go explore another aspect of the source of human behaviors: personality traits, which would make for another full article, like the OCEAN (or Big Five) approach.

You could also look into the Over-justification effect, that dives deeper into the relationship between Extrinsic and Intrinsic Rewards, and particularly how the expectation of an extrinsic reward will diminish a player’s intrinsic motivation.

Our future articles here (and probably quite some discussions on our Discord) will often reference these theories and their applications, and we will have plenty of opportunities to dive more into their practical aspect. In the meantime, try and think about our last theory, the PENS, and how your current game could benefit from it.

Always remember that meaning is the most powerful motivator and that the more we design games answering core human needs (and not only tickling their lizard brain), the more meaningful and powerful games we will make.

Do you want to get regular quality articles on Game Design and join an awesome community of devs and designers on our private Discord to discuss design, learn, and review each other’s games? Then consider supporting GDKeys.

Not to hijack this enriching article, but when reading and getting to Bartle’s taxonomy I really think there’s much more below the surface. Most of the people I met in the industry doesn’t know how to translate these models into practical components and technics. That’s why I wrote a guide of how to take Bartle’s player type taxonomy into practice, demonstrating the various components that can appeal to the different players’ motivation:

https://uxdesign.cc/designing-your-game-mechanics-based-on-player-types-b16a95fb7f60?gi=7acd512e52d0